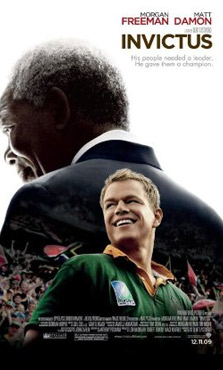

“Invictus” is the sort of sure-handed, efficient, crowd-pleasing sports film that would crown the careers of many directors. For Clint Eastwood it’s just another quietly and smoothly effective drama to add to his legacy. Always an actor’s director first, Eastwood gets excellent performances from Morgan Freeman as Nelson Mandela and Matt Damon as Francois Pienaar, the two central figures in the near-miraculous resurrection of the South African national rugby team in 1995. The story might seem wearyingly familiar—personal redemption through team sports—but Anthony Peckham’s screenplay (from John Carlin’s book) has the appealing virtues of being based on a true story and skillfully using the stoicism of its leads as ballast against the menace of a feel-good rah-rah sports flick. The bad news ‘Boks have their day, but the film opens up a seam of truth inasmuch as Mandela’s interest in the team is as much cold calculation as it is a quest for redemption.

The central scene in the movie is the meeting between Mandela and Pienaar. Mandela’s presidency is off to a shaky start. Though revered among the black population, he feels as if he may lose the minority white population, as well. A unified South Africa is what he wants, and the Springboks offer a chance to bring the populace together to cheer them on in the World Cup. Fascinatingly, throughout the film Mandela maintains an inscrutability that keeps shifting coordinates, moving between a stoic engagement with his advisers in some scenes and bottled-up passion in others. The meeting with Pienaar is gripping because it is not a rousing moment though it ought to be; Pienaar arrives, sits with the president for a cup of tea, listens to him speak briefly about the importance of the team, and that’s it. The men sit across from each other somewhat stiffly, magnetized by the moment yet unable to have a dramatic personal exchange. Freeman and Damon radiate the circumspection and the diffidence of whites and blacks, as well as the simple awkwardness of a rugby captain meeting a head of state—yet a will to unity, national pride, and goodwill are also present between them. It’s a superbly acted scene, conveying in clipped sentences and pregnant silences all of the story’s contradictions and complexities.

Though Freeman gives the obvious Oscar-worthy performance with his eerily accurate impersonation of Mandela, Damon is a solid match. His Pienaar is the strong, silent type—and to Damon’s credit he lets him actually be a strong silent type. Actors of Damon’s stature don’t thrive in roles that require them to keep their mouths shut rather than mumble corny dialogue about how they prefer to keep their mouths shut. Damon’s rugby captain is a tender brute with no silos full of electrifying speeches waiting to be raided right before the big game. Nothing appears to be kept back, which makes him more, not less, interesting. But then this isn’t surprising to see here, considering that Eastwood’s legendary Spaghetti Western cowboy was practically a silent film star (and perhaps Damon simply preferred to speak as little as possible, given the challenge of an American pulling off a South African accent). In any case Damon does a fine job embodying the demeanor of the white South Africans who neither welcomed nor opposed the end of Apartheid: stunned by the sudden uppercut of history, wondering what the next swing will bring.

The grace and gravity Freeman and Damon provide the film give the more conventional elements of the story a longer leash, as it were. For instance, when Mandela takes power, it is Freeman who gives Mandela’s adamantine insistence on unity among his staff both solidity and poignancy; the decrees he makes to his subordinates sound like executive decisions and heart-tugging pleas, stern commands and humble requests, at the same time. Mandela paradoxically seems to wield enormous power and very little power, which is perhaps an historically astute observation. But alongside these tremendously complex dynamics are clumsy ones: his security team is—get this!—made up of blacks and whites who don’t like each other at first. And yet, and yet—would you believe it?—late in the film, in the excitement over the rugby team’s success, they bond over an impromptu session of rugby out on the lawn! Such is one of a few examples of the kind of cardboard set-ups with which Eastwood surrounds the film’s solemn complexities.

It’s a testament to Eastwood and his actors that the latter don’t sink the movie, because the hackneyed drama of the security detail is just one of several subplots that hover around cliché. There’s the poor black kid who learns to coexist with intimidating white cops, the black housekeeper who gets a ticket to the big game, an airline pilot who risks his job to show support for the Springboks, empty streets in villages and neighborhoods where tiny rooms are packed with people watching the World Cup on TV, etc. The rugby matches are boilerplate sports-flick fare, complete with a soaring score and the Evil Team led by the grunting Superman (though, it must be said, these scenes are shot expertly by Eastwood, who makes the sport easily intelligible and uses sound and editing to create electrifying sequences of bone-crunching, sweat-soaked rugby that make American football look like croquet in comparison). To counter these, Eastwood keeps going back to the well, drawing from the power of his two leading men to level the film and keep it leaning toward genuine drama and not manipulative pap.

The oscillation between adroit drama and conventional feel-good story suggests an interesting theme. Mandela’s motivations are difficult to read. He is, at once, a grizzled survivor clinging to the hard-won spiritual empowerment wrested out of his brutal imprisonment and a shrewd statesman whose decision to resuscitate the ailing national team is primarily an act of impersonal strategy. Eastwood seems to suggest an odd duality to the Springboks’ success,not that far removed from the anxieties about the media in “Flags of Our Fathers”: how closely allied are politics and showmanship? Eastwood, of course, is uninterested in depicting these historical events as “postmodern spectacles”. Mandela and Pienaar are too soulful and the scenes of rapprochement among whites and blacks too earnest, among other things. Nevertheless a space opens up between Mandela and Pienaar, on the one hand, and everyone else in South Africa, on the other. The two principles understand the political nature of the problems of the day and attempt a political solution. The stage is the thing; the sports, the songs, and all the rest merely props in a necessary ritual. It’s these less telegraphed themes in “Invictus” that make us feel good about cheering the blunter ones—and cheer we do. |