|

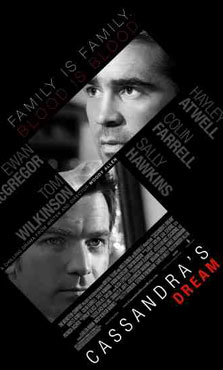

The title of Woody Allen’s latest, “Cassandra’s Dream”, with its reference to the doomed Greek prophetess, neatly encapsulates everything good and bad about the film itself: bad, inasmuch as Cassandra or anyone like her—much like the legendary director whose name also features on the poster—is noticeably absent, such that the general sense is the movie is hollow product trading on a brand name; good, inasmuch as the film needs the thin patina of Greek tragedy to suggest themes larger than itself, without which it would be pitiably meager. Weirdly, the movie is both more and less than it appears, and how much you see in it, like the proverbial glass of water, is up to you. Though his choice of younger actors and fresher settings argue the opposite, Allen has grown increasingly indifferent to life outside his pet obsessions. If ‘Dream’ stands apart, it’s in the dialogue, which is the least Allen-esque, least ventriloquized since 1978’s “Interiors”. The title of Woody Allen’s latest, “Cassandra’s Dream”, with its reference to the doomed Greek prophetess, neatly encapsulates everything good and bad about the film itself: bad, inasmuch as Cassandra or anyone like her—much like the legendary director whose name also features on the poster—is noticeably absent, such that the general sense is the movie is hollow product trading on a brand name; good, inasmuch as the film needs the thin patina of Greek tragedy to suggest themes larger than itself, without which it would be pitiably meager. Weirdly, the movie is both more and less than it appears, and how much you see in it, like the proverbial glass of water, is up to you. Though his choice of younger actors and fresher settings argue the opposite, Allen has grown increasingly indifferent to life outside his pet obsessions. If ‘Dream’ stands apart, it’s in the dialogue, which is the least Allen-esque, least ventriloquized since 1978’s “Interiors”.

The theme of Allen’s film is Greek only if tragedy means nothing more than a body count. With so many texts lost to posterity we can never really be sure, but it’s probably safe to say there are no ancient Greek tragic heroes who find themselves in a pickle thanks to a rough night at poker down in the Piraeus or an impending business deal to build kebob huts in Elysium. No, the real presiding spirit is Dostoevsky’s, of course, and it’s strictly existentialism by numbers. Murder? Unpunished. God? Uncommunicative. Dramatic ironies? In spades, though nothing as rich as an opthamologist realizing the cosmos is blind (“Crimes And Misdemeanors”).

The acting saves the day, however. The movie belongs to Colin Farrell as Terry, the more soulful half of a pair of jumped-up working class boys who do everything together except shop for suits. Drawn into dire circumstances by a penchant for gambling and the masterful economy of Allen’s plot, Terry suffers a crisis of conscience which Farrell rather nicely evokes by upramping his lavish eyebrows until they make of his rugged face a permanent emotional hieroglyph (similar to a car’s hood ornament, perhaps, or the Atari logo).

Ewan McGregor as Ian, the dashing older brother with the big dreams and the tiny scruples, is a million miles away from the sparkling-eyed scamp of “Shallow Grave” or, for that matter, the dead-eyed junkie of “Trainspotting”. McGregor seems too polite for the material. In an amusing way his performance here closely resembles his respectful Alec Guinness impression as Obi Wan Kenobi in “Star Wars”. Like a few other actors, such as Nicolas Cage, it is always instantly and disappointingly apparent when the role he’s chosen has failed to kindle his passion. McGregor is certainly passable as Ian, the cooler-headed “brains” of the operation, but rarely does Allen get from him the necessary hint of loosely-leashed savagery. Jonathan Rhys-Meyers, the killer in Allen’s best British movie to date, “Match Point”, may have lacked credibility as a heterosexual love interest but the cold spark of murderous ambition was always visible in his eyes. Even as a petty thief taking cash out of his father’s safe McGregor appears utterly lamblike. He is unimaginable as a California hotelier-playboy and consequently his motivation to commit the central crime comes across as weak.

Allen’s script is a clockwork that tolls its bells at all the right points but never escapes the momentum of a mechanical device. The story lacks springiness, menace, jutting edges. Noticeably absent is one of Allen’s favorite stock characters, the Woman On Edge. The WOE is a sexpot who all too quickly turns into a fire-breathing harridan, tipping the moral scales against the transgressing male as easily as their flailing hands might overturn a martini glass in mid-bellow. “Match Point” had Scarlett Johanssen as the flighty, headstrong American while ‘Misdemeanors’ benefited from one of the cinema’s great mistresses, Angelica Huston, a woman scorned who made hell’s fury look like a carnival ride.

No such character exists here to stir the plot to a blood-curdling pitch. Newcomer Hayley Atwell simmers forth with the sex but not the crazy; in her penultimate scene she rather boringly admits she loves Ian, choosing McGregor over wealthy, well-spoken Lord Something-or-Other, which just proves the awesome bird-pulling power of a man who restores and pilots his own sailboat. Instead the movie tiptoes onward, morosely wringing its hands. For his killers Allen should have looked for inspiration no further back in history than Beckett or Brecht. His anxiety-clenched “breaking God’s law” monologues sound anachronistic and uncharacteristically tin-eared.

Despite these flaws “Cassandra’s Dream” is redeemed by its excellent cast. Besides Farrell, who gives a strong performance, Tom Wilkinson is bracing as the stoop-shouldered Uncle Howard, an oily, rodent-eyed millionaire who reeks with exactly enough sleaze to suggest to the audience how far he’s come to reach the top and more importantly what got him there. Ashley Madekwe looks like she was cast because of her resemblance to Allen’s current muse, Johanssen, but she proves a much livelier actress. John Benfield and Clare Higgins drop enough aitches to ground the story. And, as always, Allen, even in an off outing, seems incapable of making bad movies. Though at times “Cassandra’s Dream” seems like a precis of a better Allen film, dramas with adult themes like this one are few and far between (even counting the recent—and superior—“Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead”, which has a similar plot). The fact that Allen is so obviously out of touch with the zeitgeist gives his philosophical inquiries that much more weight. A man Terry’s age would never say the things he does, but on the other hand it’s not candy-coated disco nihilism, either. Allen knows how to make the story’s moral weight sink in, and that’s a pleasure in itself. Assaulting the audience with machine-gun editing, trendy despair, and zippy one-liners, as do most contemporary movies, would be a tragedy. |

|