The subtle innovation of Werner Herzog’s “Rescue Dawn” is that its hero, Dieter Dengler, does not suffer a gradual stripping away of his personality as the months of his captivity limp and crawl ahead, but instead emerges from his ordeal more or less the same man he was when it began. Prison camp movies usually depict a man undergoing a string of traumas that batter him backward to his most essential, indeed feral self. In the hardest, most terrifying cases, the construct of “self” unravels altogether. Christian Bale’s first and best prison camp movie, “Empire Of The Sun”, plotted exactly that course for its embattled young dreamer. Dengler, with his love of airplanes, could even be the older version of young Jim from Shanghai, now living his dreams of flight. Dengler’s even the right age, and his description of the American pilot looking down at him on a low fly-by—“He looked straight at me!”—could have come straight from Ballard’s book.

“Rescue Dawn” has more in common with a fantasy like “The Shawshank Redemption”. Call it the “glass half full” vision of prison: the endless degradations of the military holding cell shatter and scatter some men to the four winds, but others, because of physical toughness or brute stupidity—or a bottomless inner spring of hope, fed by waters native only to Hollywood—leave captivity as they entered it. Like Andy Dufresne, Dengler, spiritedly confident and always eager to roll up sleeves and occupy his hands with a task, sets out to free himself as if resignation to the cruel circumstances of his fate were as alien to his mind as, say, reciting a chapter of “Ulysses” in Mandarin Chinese.

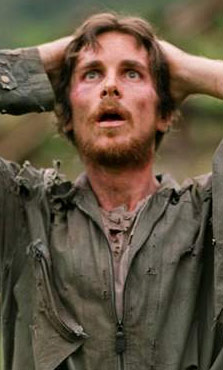

Indeed, though German-born, Dengler is almost a parody of post-war American know-how and industrial-strength optimism. The grimmest obstacles are merely problems to be solved with no more agitation than balancing a checkbook. When he vows revenge on the guards, it’s because they’re not playing by the rules he somehow believes still govern them all. He doesn’t even seem to be affected by the food shortage. Knowing Bale’s body of work, it would naturally be expected that he would show off the stunt emaciation he carried off so wincingly in “The Machinist”, when he looked like a stick insect flattened by a boot. But though Bale eats a bowl of worms and later a snake, demonstrating that he’s willing to do what it takes to nourish himself, his comparitively robust physical stature seems more like an unconscious act of will than a liberal diet.

Dengler’s aura of untouchability makes Herzog’s film seem slightly unreal. Starting with the plane crash itself, in which Dengler walks away unscathed despite hitting a rice paddy at full speed, and continuing through the torture, barefoot tramping over miles of thorny land, and starvation rations at the camp, to the relative ease with which he navigates the incredible density of the Laotian jungle, Dengler never seems overly taxed by his surroundings. At times he has the demeanor of a sleepwalker.

When his hero does confront reality, Herzog never lets Dengler slip into superhero invincibility. In fact the oddly affecting strength of “Rescue Dawn” is its stoicism. Dengler’s power comes not from ignoring the frighteningly immediate prospects of his own suffering and his possibly vicious liquidation, but rather his insistence on doing everything within his reach to avoid that fate, no matter how small the job seems. Dengler dreamily mentions “the quick and the dead” at one point, so he might also have known Ecclesiastes: “In the morning sow thy seed, and in the evening withhold not thine hand: for thou knowest not whether shall prosper, either this or that, or whether they both shall be alike good”. Work and hope, but work first.

Of course, the Bible is probably a bad reference point for Dengler’s frame of mind. When asked on the safety of the U.S.S. Ranger if “God or country” got him through his trials in the Vietcong camp, Dengler has no answer. Perhaps the recently-rescued Dengler is still in a daze when he is asked for this public relations soundbite, but Dengler seems ontologically puzzled by the question. When he does speak, the advice he gives starts off like Eastern mysticism. “Fill what is empty. Empty what is filled.” Then Bale adds the rest like a perfectly timed punchline: “Scratch where it itches”.

Dengler was talking about filling stomachs and emptying bladders—and bug bites. This is the simple clarity of one of Rousseau’s savages. Dengler survives because he thinks first and foremost as a human animal in full and happy possession of its instincts. America, which Dengler clearly loves and admires, is loved and admired mainly because it was in the U.S. Navy that Dengler was allowed to realize his childhood dream of flying, not its democratic tradition. He loves America despite his tiny Black Forest village being bombed by U.S. planes in raids Dengler himself calls “pointless”. His prison-camp buddy Duane (Steve Zahn) remarks on the irony of his love of flying coming from an American trying to kill him, but Dengler looks as if the thought had never occurred to him.

Herzog doggedly insists on assaying Dengler’s mentality, though. Audiences may not see it. By the end it seems like Dengler survived in spite of his mind, not because of it. The disconnect in “Rescue Dawn” between the director’s more arid observations about Dengler’s political crucible and the downed pilot’s actual flesh-and-blood struggle to stave off death makes for a decent but curiously self-contradictory movie. The visceral remains strangely concealed from Herzog. He seems more interested in whatever it is he thinks supplies the twinkle in Bale’s active eyes, eyes that seem to glide on horizons undreamed of by the other inmates, when in fact Dengler was probably thinking about the best way to fashion a bamboo shoot into a digging tool or the nutritional content of a caterpillar.

Dengler’s escape brings us satisfaction, even some elation, but it’s hard to celebrate an escape from a prison we never felt we knew. There is more synergy between the film’s conceptual and cinematic dimensions in Dengler’s slapstick getaway from the CIA than in his flight from the Vietcong. Even as his hero endures the most basic and brutal hardships to stay alive, for Herzog prison and war are nothing more than ideas. The meaning of Dengler’s last freeze-frame smile seems to have eluded the man telling his story. |