|

Chan-wook Park’s “Oldboy” springs out of the gate with exhilarating speed. Rapidfire editing, original camera setups, and grimy, flat lighting introduce us to Dae-su Oh, a man imprisoned for mysterious reasons in an urban dungeon in Seoul. The instantly enthralling mystery spikes out in jagged chunks like a coked-up, noir version of “The Count of Monte Cristo” (which Park openly alludes to at one point). As in some other recent twists on the noir revenge genre like “Insomnia” or “The Machinist”, which use the form to spin existential mindbenders, the movie becomes a twilight zone more of the mind than the body. There are scenes of creepy desert-island style madness as Dae-su wastes away in his living room prison, watching TV under the gaze of a bizarrely gruesome portrait of a weeping man that would have made Grunewald squirm. Tom Hanks had it lucky. A punctured volleyball beats daytime TV any day. From the beginning Park finds humor in unexpected places. In one scene, Dae-su loses his temper and smashes the glass on a painting, slicing his hand in a nod to “Apocalypse Now”. Immediately after, we watch from the ceiling as Dae-su, unconscious, is dragged from his room by his captors, his limp hand painting a trail of red across the floor. Later, after another fit, Park only glances at Dae-su’s rage before quickly cutting to another dragging, another pool of blood on the ground. The stains, which are not washed, become emblems of futility. Unable to kill himself, the net result of Dae-su’s rebellion is merely a series of ugly brown stain on the floor. Chan-wook Park’s “Oldboy” springs out of the gate with exhilarating speed. Rapidfire editing, original camera setups, and grimy, flat lighting introduce us to Dae-su Oh, a man imprisoned for mysterious reasons in an urban dungeon in Seoul. The instantly enthralling mystery spikes out in jagged chunks like a coked-up, noir version of “The Count of Monte Cristo” (which Park openly alludes to at one point). As in some other recent twists on the noir revenge genre like “Insomnia” or “The Machinist”, which use the form to spin existential mindbenders, the movie becomes a twilight zone more of the mind than the body. There are scenes of creepy desert-island style madness as Dae-su wastes away in his living room prison, watching TV under the gaze of a bizarrely gruesome portrait of a weeping man that would have made Grunewald squirm. Tom Hanks had it lucky. A punctured volleyball beats daytime TV any day. From the beginning Park finds humor in unexpected places. In one scene, Dae-su loses his temper and smashes the glass on a painting, slicing his hand in a nod to “Apocalypse Now”. Immediately after, we watch from the ceiling as Dae-su, unconscious, is dragged from his room by his captors, his limp hand painting a trail of red across the floor. Later, after another fit, Park only glances at Dae-su’s rage before quickly cutting to another dragging, another pool of blood on the ground. The stains, which are not washed, become emblems of futility. Unable to kill himself, the net result of Dae-su’s rebellion is merely a series of ugly brown stain on the floor.

Humor like this in a revenge tale is amusing and adds a measure of uncanniness to Dae-su’s story. In this Park borrows a little from Tarantino, who delights in mixing tones and genres into his crime potboilers. But he has a wider spectrum of colors on his palette than Tarantino, and is closer in some respects to Cronenberg. Explorations of altered states of consciousness mix with the raw vulnerability of flesh and blood. His style is both impressively concrete and deploys a fluid, almost restless intelligence. In one scene, Mido, the lover, gives a monologue about loneliness. She commiserates with Dae-su’s hallucinations about ants running over his flesh, and says that the haunted imaginations of lonely people typically conjure ants as a symbol of their condition. To illustrate the point, Park shows Mido on a subway, alone and forlorn, until she realizes she’s sharing a train with, yes, a giant ant slumped forward on its seat. Proof that subways can sap the spirits of any creature, I guess; I was slightly disappointed that Park didn’t have the thing nodding off to a Michael Chabon paperback.

This is more than an indulgent detour, as it might have been in the hands of, say, Guy Ritchie. As a filmmaker Park is driven by a hungry promiscuity that wants to explore multiple perspectives. The clash in his style reflects the difference between the two leads. Dae-su’s way of looking at the world is narrow and literal, Mido’s expansive and metaphorical. Dae-su knows and feels the objects around him in the most direct way. His story fascinates because he is moving up the ladder toward his tormentor, one rung of the ladder at a time, as in any mystery, but rather than going from clue to clue he does it on the most minute level—second to second, object to object, room to room: a pair of scissors, a hammer, a page torn out of a phone book become catalysts. Like John G. in “Memento”, he has no sense of time, either past or future, which ultimately determines his fate. Mido has the wider view. When she is faced with the same gift-wrapped present Dae-su is, she weeps in terror at the thing, fearing for what’s inside. She has the imagination to feel terror, but Dae-su, who opens the box as perfunctorily as a boy doing another arithmetic problem, does not. Park’s lively contrast between the two characters throws the picture of Dae-su’s solipsistic madness into deeper relief and yet, equally interesting, serves the story by providing emotional links between Mido and Dae-su that later become important.

Smaller set-pieces of Park’s visual style are set like gems throughout the movie. There is a three-part sequence after Dae-su is released that is as good as any movie released this year. First, the suicidal man Dae-su meets on the rooftop listens to his long tale of woe, deeply interested. But as he starts to tell of his own sorrow, Dae-su leaves him, insensitively walking off without hearing the man’s story. We leave him on the roof, following Dae-su. On the elevator going down, we see a nervous-looking woman with odd-looking glasses. Park slowly pans right, revealing Dae-su backed into his corner, like a cat two inches from water, calling up every ounce of strength left in his body not to rape the woman. When he exits, he’s got her glasses on, and she’s yapping at a constable to lay the hands of the law on him as Dae-su walks out of the building on the street below. Suddenly the suicidal man returns to the scene by plummeting to his death behind Dae-su, smashing through the roof of a parked car, his toy dog bouncing off the crushed metal. Dae-su makes it as far as an alley before he runs into trouble, a gang of fresh-faced punks who jump him. “Can fifteen years of imaginary training be put to use?”, Dae-su asks in voiceover. He leaps into the fray, landing expert, devastating chops and punches on his attackers’ shocked faces, just as Park serenely fades out. The voiceover returns: “It can.”

The film is built on these small, highly cinematic moments when a character and his story are constructed out of scraps of dialogue, some mood music, clever montage, and bold scene-setting. The combinations Park finds are poetic. He also shows off tremendous wit in echoing earlier scenes and details later in the movie. The screenplay doesn’t live up to his style, unfortunately. It’s not so much the unusual twists; implausibility is nothing foreign to movies like this. “Chinatown” is as baffling after a handful of viewings as it is after the first. But “Oldboy” hums along beautifully only until Dae-su starts to immerse himself deeper in his own mystery, at which point the burden of exposition overpowers Park’s fleet-footed attempts to sustain the film’s mood and energy. Not only is there too much talking, but the revelations are so starved of inventiveness that they border on the banal. Clearly planned this way, “Oldboy” makes a point of down-scaling the dimensions of its story as part of the mystery. There’s precedence for this. Tarantino built “Pulp Fiction” using similarly everyday, smallish details such as a lost watch, a dirty car, a syringe, and a gangster going out for donuts.

But Tarantino’s camera in “Pulp Fiction” is actually calm and watchful. Action comes in quick bursts; most of the pyrotechnics are in the dialogue. Park’s style is unsuitable for his story’s prosaic conceits because the editing is much nimbler, his eye for setups more vividly askew. His imagination is visually unrestrained. Tarantino’s films are as <i>written</i> as they are filmed. Park wants to escape the script and exult in a realm of pure motion, gorgeous still shots, and witty montage. “Oldboy” has a speeding pulse that simply laps the script several times over. Frankly, the climactic scene in which Dae-su squares off with his nemesis, which goes on far too long and is engorged with dialogue, is insipid. It makes little sense psychologically and ends the mystery with a thud. Yet Park surprises in the middle of the scene with a fantastic cut-away to the outside while Dae-su is flung against the plate glass window in a fight, or when Dae-su swabs the evil henchman’s ear with a pair of scissors. These are reminders of his considerable talents, and illustrations of how good his films might be were they freed from the constraints of a byzantine plot.

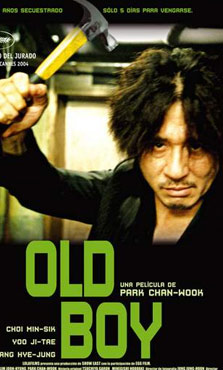

The story is an honorable mess, though. “Oldboy” deserves credit for not only its visual style but its willingness to appropriate various genres of literary storytelling. Park used a variety of models, including the obvious ones like Chandler and Dumas, but also Burroughs, Kafka, and bits of “Oedipus Rex”. (There’s also a subtly placed but rather bald joke: the suicidal girl is reading Sylvia Plath in English a few scenes before her exit.) Movies like this often devolve into the same old existential riddles, one the same as the last, but Park apparently threw off all the fetters of the noir revenge tale and made a unique, if flawed film. His cross-fertilizations feel natural, never forced. With this, his fifth film, and winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes, Park has announced himself as a major talent. Whether or not he fritters it away on bloated scripts like “Oldboy” remains to be seen, but his dazzling cinematic style is cause for hope. Hard to imagine sitting through repeated viewings of this film, or ever coming to love it, but watching it leaves one with an inescapable conclusion. This is what movies are all about. |

|