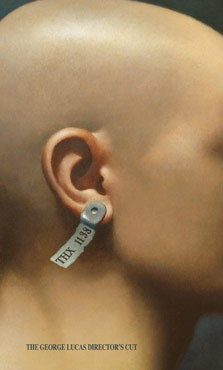

“THX-1138”, the forgotten precursor to George Lucas’s blockbuster space operas, is almost impossible to judge on its own terms. Every frame contains either the rudiments of images that would eventually find their way into “Star Wars”, or a stillborn idea that points to another, alternate filmic universe in which Lucas did not become the highest paid hack in the history of moviedom. “THX-1138”, the forgotten precursor to George Lucas’s blockbuster space operas, is almost impossible to judge on its own terms. Every frame contains either the rudiments of images that would eventually find their way into “Star Wars”, or a stillborn idea that points to another, alternate filmic universe in which Lucas did not become the highest paid hack in the history of moviedom.

Some details resonate more technically; listening carefully, it’s possible to distinguish the sound effect that would later become famous as part of Lucasfilm’s ubiquitous surround-sound system. But even if one diligently imagines viewing “THX-1138” in a pre-Ewok world, the burden shifts away from the movie’s portents over to the elements of which the film is composed: “2001” and “1984”, “Metropolis” and “Alphaville”, to name the obvious.

This is unfair. After all, Lucas came up with an intriguing film that has some strikingly original textures. Thanks to the astonishingly rich sound montage by Walter Murch, as subtle and integral as his later work in Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now”, “THX-1138” is a neatly composed, multilayered quilt of digital sprawl. The flawless interplay of image and sound is immersive and creepy, highlighting a strength that would serve the “Star Wars” franchise so well. Lucas effectively captures a cyberpunk flavor that stubbornly refuses the status of coolness.

The film fetishizes the blurts and bleeps of his mech-world while simultaneously revealing the mundanity of this bureaucratic inferno. It’s all ones and zeros: the film depicts not only a political dystopia but a technological devolution. For all the wonders this future society has created, it has succeeded primarily in institutionalizing mediocrity. The institution, the state, is at once the best and worst aspect of “THX-1138”. Superficially it’s more of the former. Lucas’s script uses a language comically scrubbed of all humanity, replete with bureaucratically sanitized speech. The dialogue might seem awful—wooden, untactile, tinny, recalling Harrison Ford’s comment that Lucas “could type this shit but you sure can’t read it”—but for once Lucas’s words fit the world he created.

The exploration of an Orwellian dystopia, this film confirms, is exactly Lucas’s sweet spot. (Consider these gems of redundancy from “The Phantom Menace”: “No need to report anything until we have something to report”, “Roger, roger!”) Citizens “confess” to a Big Brother-type priest who exhorts his flock to “Buy. Buy more. Buy now. Be happy!” Drugs-taking is mandated by law, Oceania’s surveillance cameras placed inside the medicine cabinet along with an aspirin-commercial voice that asks “What’s wrong?” when the door swings open. Given our present-day dependency on “normalizing” drugs, this was a most prescient touch by Lucas.

On a more practical level, you don’t need zippy dialogue when all the characters are thoroughly medicated. Donald Pleasance’s twitchy, childlike SEN, for example, is a character worthy of Terry Southern. Full of homoerotic non-sequiters, this “tweaker” of the rules has the movie’s most hilarious scene, in which he tells THX that he has arranged for the two of them to become roommates. “You scored very highly in hygenics,” he beams. The best lines come from characters we never see, the disembodied voices of the magistrates. I particularly loved the scene in which two techies discuss how the prison’s torture chamber works. While Duvall’s THX writhes in agony in his cell, they casually discuss the frequencies and settings of the machine that’s sending searing pain into his body, as if attempting nothing more serious than adjusting the levels on a stereo tuner. Undoubtedly this, too, is an accurate forecast of the future, a Windows-world in which tyrants will talk not of brainwashing or re-educating their masses but of installing new drivers in their heads.

Beneath these apt and frequently humorous moments, however, Lucas fails to offer any satisfying critique of the modern security state. “THX-1138” is anything but a hippie film, but it has that annoying hippie capacity to catalogue the symptoms of a sick society while displaying absolutely no knowledge of how things got to be the way they are. Lucas’s vision of the future seems more like a flight of fancy among marijuana clouds than the result of serious thought. The main idea seems to be that the state’s power is mitigated by its decentralization: no one’s behind the wheel in Lucas’s world. But that doesn’t jibe with what we know about the abuse of power. Someone benefits from the controlling superstructure, whether it’s the self-deluding underling or the evil overlord.

This was well-known to the authors of “1984” and “The Time Machine” (which the movie also evokes), and even Lucas would later create his mastermind Emperor. By not digging further to identify the source of all these ills, “THX-1138” has a frustrating lack of conviction—it isn’t funny enough, not trenchant enough to score a direct hit in a political or social sense. In this Lucas differs markedly from the contemporary satires of Southern or Paddy Chayefsky.

The difference is in the eye candy. Lucas just has too much fun with his high-tech inventions. “THX-1138” only pulsates with real energy during the climactic chase scene in which THX makes a run for the surface. Here, too, we see the germs of future Lucasian obsessions: street racing in “American Graffitti” and the pod racers and land speeders in “Star Wars”. Interestingly, there’s nothing futuristic about the vehicle THX drives. It has tires and a steering wheel, and the chase itself is right out of any third-rate action film (somehow, in a dark tunnel leading to nowhere, Lucas included the equivalent of the chasing car smashing through a fruit stand).

In short, the scene sheds the “art school” patina of the previous ninety minutes. Lucas always flirts with human interest, with art, but in this film, as in “Star Wars” (especially the Prequel Trilogy), Lucas can’t help himself when the gizmos come out. To the detriment of his characters, at every turn he betrays his boyish, tunnel-visioned fascination with technology. Taking on totalitarianism is small fry compared to a fast set of wheels. |