|

We’ve seen movies fashioned after video games, or, conversely, movies that were obviously made just to spin off a video game, but, the James Bond franchise notwithstanding, I don’t think there has yet been a movie created as a car commercial. In matching slickness to purpose, “The Italian Job” is reminiscent of the short, web-only film John Woo shot for BMW, starring Clive Owen in a race-against-time kidnapping story. Here the hero is a Cooper Mini, and five minutes don’t pass in this movie without seeing a shot of one gracefully sliding in and out of traffic like a brightly-striped croquet ball darting through pale shrubbery. I half expected a silky voiceover to announce that I could acquire one for no money down and get cash back for a limited time only. We’ve seen movies fashioned after video games, or, conversely, movies that were obviously made just to spin off a video game, but, the James Bond franchise notwithstanding, I don’t think there has yet been a movie created as a car commercial. In matching slickness to purpose, “The Italian Job” is reminiscent of the short, web-only film John Woo shot for BMW, starring Clive Owen in a race-against-time kidnapping story. Here the hero is a Cooper Mini, and five minutes don’t pass in this movie without seeing a shot of one gracefully sliding in and out of traffic like a brightly-striped croquet ball darting through pale shrubbery. I half expected a silky voiceover to announce that I could acquire one for no money down and get cash back for a limited time only.

Actually, more than a car commercial, “The Italian Job” plays like a tepid first draft of a truly twisty caper— and if it is likable it’s only because it seems like the tepid first draft of a master. If we are ever treated to The Complete Works of David Mamet, one of his earliest, forgotten works would probably read like “The Italian Job”. It would be located not within the main body of work but filed under something like “Appendix: Juvenilia”, and only graduate students would peruse it. Peeking over Mamet’s shoulder, one would expect to see him start where this film ends, getting out his red pencil, slang dictionary, and cocktail napkins, ready to figure out how this thing could really hum— where to put the trompes l’oeils, how to sneak in the legerdemain, and calculating how many onion-skins the plot can sustain (and then doubling them).

“The Italian Job” takes the wrong turn early on when Charlie announces that Frezelli, the villain, is only notable for his overwhelming lack of imagination. This is ironic, since Edward Norton, in it for the paycheck, turns in a listless, uninspired performance of his own. Anyway, his Charlie spends ninety minutes intent on proving the truth of his initial assessment, relying on Frezelli’s dimness to stage a leisurely heist that could have been done painlessly with a chloroformed rag and a tranquilizer gun halfway into the movie. Charlie’s idea of imagination, it seems, has much in common with Tom Sawyer’s nugatory machinations in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Why settle the obvious solution when you can have so much fun proving how complicated you can make things? There is something endearing about a bunch of thieves who rig up bombs to blow a hole in a city street just to have an armored car drop into an underground tunnel, there to be plundered without incident, but I admit I preferred Frezelli’s hardscrabble method of carjacking. In fact, by the end I was almost rooting for him to use his blunt force to out-smart, so to speak, these fancypants Gen-Y con artists who pointedly refer to their vehicles as getaway cars. But no such luck. Frezelli really is that unimaginative, but that was obvious as soon as he fails to find anything unusual about a supermodel showing up to fix his cable box.

Of course, that’s the problem with the film as a whole— it’s a confection, alright, but it’s strictly vanilla. Aside from Donald Sutherland, the gang assembled in Venice might as well be a gaggle of college students traveling Europe by rail. This is by design, as elegant, victimless thievery is the one anti-corporate profession most suited to our nation’s idealistic youth, those uncompromising twentysomethings who want a paycheck and a little soul, too, thank you very much. Still, I suspect audiences will always prefer naked, panting greed over, say, a character motivated by a whimsical notion about owning a library full of first editions and “a room just for shoes”; Tony Montana would have had these kids out front parking his Ferraris. Most telling of all, when “The Italian Job” makes its jump to television, the network censors can take the night off on this one. Not every film must have Scorsese’s crunchy violence or Tarantino’s toothsome vulgarity, but for heaven’s sake when you’ve taken the trouble to introduce a 400-pound Samoan named Tiny Pete who peddles “chemical grenades” you might as well get some use out of him. Alas, after Tiny Pete is threatened by an ax-wielding thug, he fearfully uses terms like “that mother-freaking Ukrainian” to describe him, and one can’t help pining for a few good old-fashioned four-letter words. Some spicy profanity might have helped a movie whose most outrageous statement is the mumbled suggestion that Kennedy stole the 1960 election. Instead, the writers regale us with asides on NAFTA and the genocide visited on “indigenous peoples” by those wicked Europeans. No doubt the spotted owl speech will show up on the DVD.

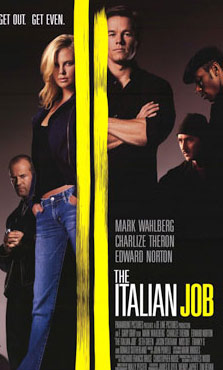

“The Italian Job” isn’t bad so much as it is weightless and benign, but for crime films that’s just as bad as being, well, bad. The characters are affable enough, though, to keep interest from waning. Mos Def looks ready to start a profitable acting career, Jason Statham does a good job showing off how British he can be, Charlize Theron is a skin-care commercial in high heels, and Seth Green keeps the laughs coming as the computer whiz with a microchip on his shoulder. The always solid Mark Wahlberg breezes along well enough, the only serious strain on his acting muscles coming when he must grab a basketball and sink a ten-footer with no editing.

The dud in the bunch, as I said, is Edward Norton, but in fairness he was saddled with a part that would have lost nothing played by Dolph Lundgren. Caper movies are only as entertaining as the crime bosses who spur the heroes through the plot, and Norton’s Frezelli is as clever as a bag of hammers. Nor is he vicious enough to sustain any interest, although there are one or two witty set-pieces, like the L.A. gridlock sequence, to help divert our attention. In the end, Charlie tells us that the heist wasn’t about the money as he sails off with Stella in Venice. What was it all about then? I’m still not sure, but I suspect that whatever it is has stellar MPG. |

|