|

By now it is nearly impossible to imagine any new delights to be found in Woody Allen films. Despite the always reliable dialogue, shimmering with Allen’s white-hot wit, his stories of late have been strictly dead on arrival. There is a kind of sad sterility to his art: his movies are made, released, play to the core audience, and then quickly disappear. With the exception of the sublime “Sweet And Lowdown”, his films of the last ten years or so, taken severally, seem to be less a collection of unique films easily distinguishable from each other than a willy-nilly smattering of fragmentary outtakes from his previous, better films. “Hollywood Ending” plays like a random collection of scenes cut from the satirical California sequence in “Annie Hall” haphazardly mixed with the weaker outtakes from the TV producer plot in “Hannah And Her Sisters”. They seem like “extra footage” or “deleted scenes”, the sort found on “special edition” DVDs: one watches them with only mild curiosity, and the initial bafflement as to why the scenes were cut is soon replaced by grateful relief that they were.

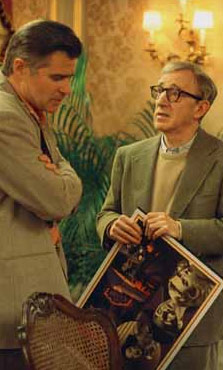

Of course, the obvious rejoinder is that Allen’s material, even the dregs of his now apparently exhausted vintage, is well worth watching. That’s certainly true of “Hollywood Ending”, which, like “The Curse of The Jade Scorpion” and “Small Time Crooks”, leaves you wondering how a movie that makes you laugh so often and so richly can utterly fail to take root in your imagination. The comedy is carefully set up, the situations, though familiar, are rendered with stout craftsmanship, and for the most part the movie has an air of breezy satire suitable for a slam on Hollywood. Whenever the studio caricatures come onscreen, led by Treat Williams and George Hamilton, the film’s pulse instantly doubles. The Chinese translator, a nervous but unnervingly well-spoken, Asiatic variation of Woody himself, steals every scene he’s in. Most of the lines are as on-the-mark as any in Allen’s other films that deal with Hollywood, despite the fact that, unlike, say, Robert Altman in “The Player”, Allen isn’t trying to dig up real dirt inside the studio walls. He is openly content to lob his smart bombs into L.A. from his loft in Manhattan, and that makes for a fresher perspective. Some of his jokes are at once outrageous and quite possibly true, such as Williams raving to Tea Leoni about a script he’s reading (“It’s about these college guys who invent a machine that turns women back into virgins”), but in other places he has an interestingly serious touch, as when Williams accepts his award from the video store owners association and begins the speech by explaining that most theatrical releases are created and hyped only to serve the video marketplace. A lot of movies give us the absurd in Hollywood, but Allen has also added a few small but genuinely chilling editorials on the state of the industry.

Indeed, if Allen had constructed “Hollywood Ending” strictly as an industry satire, he may have pulled off one of his funniest ever movies. “Hollywood Ending” is full of zingers aimed at slick, ADD-addled Hollywood bean counters whose concerns are not for art but for demographics. In one scene, Val, trying to give the right answer to his studio boss, slowly and hilariously downgrades his conception of the target audience from adults all the way to toddlers and newborns. In another, Ellie barks an order to her secretary to send flowers to Haley Joel Osment to congratulate him for his lifetime achievement award. All this forms the backdrop for a number of slapstick sequences driven by Val’s psychosomatic blindness, in which none of the Hollywood hacks catch on, a farce worthy of Terry Southern. Yet the film is by no means a farce. Eschewing total slapstick, Allen saw fit to weave a more straightforward dramatic tale into the fabric of the main comedy. This is a favorite strategy of Allen’s, one he worked to perfection in “Manhattan”, “Hannah And Her Sisters”, and, most strikingly, in “Crimes And Misdemeanors”. The levity is bled from the script by the dire consequences of the possible discovery of Val’s affliction, consequences which are reinforced at every turn. Unfortunately, the drama here— Val is still in love with Ellie, his ex-wife, and complications ensue— is relentlessly stale. Add in the subplot about Val’s estranged son, Scumbag X (which seems like an afterthought), and the movie is bogged down for much of its last hour by needless baggage. But though the movie plays like a bunch of deleted scenes for a film which doesn’t exist, Allen tells his story so carefully that the film never feels incoherent. “Hollywood Ending” merely loses steam. In so doing, however, the film inadvertently reveals something disturbing about Allen and his position as a filmmaker in the twilight of his career.

The plodding story that he takes such pains to tell, neither broad comedy or sober drama, seems less like a glaring miscalculation than it does a conscious choice. The result is a vaguely condescending subtext. With his earlier work, like “Zelig”, “Love And Death”, or even “Annie Hall”, Allen seemed willing to ask his audience to follow him someplace. The quick pacing and wall-to-wall wit in those films imply a trust in his audience. Twenty-five years ago “Hollywood Ending” would have been a fleet-footed swordsman deftly slicing its opponent to ribbons. The clunkiness of the film as it is suggests that Allen is resigned to pandering to what he thinks his audience wants. It would be unfair to say that Allen contemptuously spoon-feeds his audience, but there’s an air of defeat about “Hollywood Ending”, an unwillingness to take risks with the narrative, that suggests he’s given up the fight.

Given up the fight with whom, though? We might suppose, in light of the opprobrium he gleefully showers on Hollywood, that the fight he’s lost was between himself and the studios. But Allen has full control of his movies at Dreamworks, and as long as his films break even and turn a small profit, he has carte blanche. Studios, as meddlesome and heartbreaking as they can be for the talents they yoke to their treadmill, are— for a director of Allen’s stature— nothing more than a name and a signature on a check. Taking the acceptance of “The City That Never Sleeps” in France as a cue, Val decides to move across the ocean, ostensibly exiling himself from studio beancounters and unsympathetic critics. But really he’s running from another group of people. I was reminded of the ending of “Crumb”, of the pallor of glum disappointment hanging over the bespectacled misfit as he, too, packs for France. Crumb is not escaping from the tyranny of indifferent publishers, but from the teeming masses he no longer recognizes— his readership. The more subtle message in “Hollywood Ending” seems to be that Woody Allen is acknowledging, with unfeigned disappointment, that the fight he has lost has been with his own audience. |

|