|

|

| |

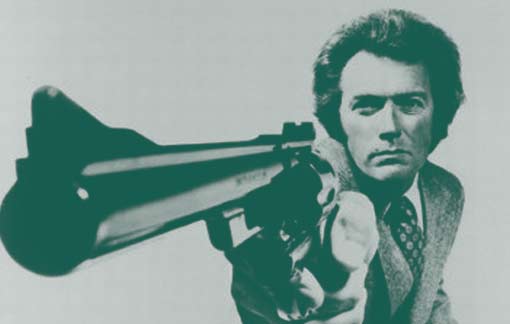

Inspector Kurtz, SFPD |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Pauline Kael famously called Don Siegel's “Dirty Harry” (1971) “a remarkably single-minded attack on liberal values” and an exercise in “fascist medievalism”. Roger Ebert concurred: “The movie’s moral position is fascist. No doubt about it”. Watching a screening of the movie at Film Forum, as part of their recent Don Siegel retrospective, I found myself thinking about these interpretations of a film I've enjoyed many times since I was a teenager. They certainly seem to have a point. What else to call a story in which the constitutional rights of a criminal (effeminate, liberal, sadistic) are trampled by a heroic cop (manly, infallible, well-hung with firearms) protecting the innocent from urban chaos with a .44 magnum?

From the first frame of the movie, when the camera pays tribute to the names of those who died in the line of duty as San Francisco cops, to Clint Eastwood's breathtaking star turn, to the crooked peace-sign belt buckle worn by the deranged killer, Siegel has stacked the deck so strongly in favor of law and order it's hard to watch “Dirty Harry” without laughing at its cartoonish depiction of good and evil. Each lurid detail of Scorpio's crackpot degeneracy ensures that we want good to defeat evil, but even more intriguingly, each example of Harry's essential integrity, juxtaposed with the spineless indecision of his colleagues, ensures that we are more interested in how “good” defeats “evil”. The cops are almost as contemptible as the crooks, and Harry's impatience with his bosses is a rich source of the film's acid humor.

Callahan himself is a walking one-liner, the model for the renegade tough guy action hero for decades to come. Here is the origin of many of the now-familiar traits: the brutal marksmanship delivered with casual ease (shooting bank robbers while chowing down on a hot dog), the lone wolf syndrome (he gets the 'dirty' jobs no one else wants), and the crippling takedown of several hoodlums in a flurry of perfectly-aimed blows (whacking three muggers on the way to deliver Scorpio's money). Eastwood's moody glare is a special effect all its own: dark, rocky ridges sucking the garish red neon of San Francisco's infernal sin factories into a furnace of moral censure.

The clash of morality with urban decadence is the central theme of “Dirty Harry”, and the questions it raises about police procedure are still timely. “Dirty Harry” is one of the first police dramas to explore the limits of law enforcement in a liberal society. On first blush, the exploration yields results that are brutal and excoriating in their intolerance, rightly earning the "fascist" labels. The law fails to punish Scorpio, the evil offpsring of a corrupt society, so Harry must do what the spineless politicians and empty suits cannot. No one can watch the film's ending without feeling that justice has been served, no matter how crookedly.

Is this really the position “Dirty Harry” stakes out, though? A clue to the answer is in Siegel's cinematic treatment of his subject. As excitingly exaggerated as Harry himself may be, the film's tone is measured and realistic. Siegel shoots San Francisco in a gritty, almost documentary style, consistently contrasting episodes of Harry's heroism with dull bureaucratic protocol. For every thrilling shot of Harry blowing away perps in comic book fashion, there are three shots of Harry doing routine detective work like climbing ladders or visiting pencil-pushing superiors for his orders. And compare the handwringing of the mayor and his lackeys to the cool detachment with which Harry correctly diagnoses a bank robbery in progress, or the D.A.'s cluelessness about whether or not Scorpio will strike again—Harry knows the city better than the SFPD brass, making him completely out of step with them.

This is important because fascism implies the sanction of the state, and Harry is clearly at odds with it. He is the goon, the grunt who does the dirty work (this is the true meaning of his nickname). In a single brilliant shot, Siegel defines Harry's relationship to the society he protects. The first chase for Scorpio ends in a football stadium. As Harry begins to torture Scorpio, pushing down on his wounded leg, the camera zooms out of the stadium, rising back into the sky, losing the two characters in a wash of light and fog. This works on two levels. One, Siegel distances us from Harry, intimating that Harry, acting in our name, is about to do the dirty work—torture—which we, the citizens, don't want to see or know about. Two, by placing the hero and the villain in a football stadium, we see them for who they really are: Roman gladiators, both outcasts, locked in a bloodsport that is somehow, though we may not know why, necessary for our civilization.

If that sounds as if I am giving “Dirty Harry” more thematic heft than it really possesses, consider that John Milius worked as an uncredited writer on the script. Milius, of course, is our Hollywood Homer, responsible for the shameless valorizing of the American warrior in all his splendid variations, most notably in the brash adaptation of “Heart of Darkness” which became Francis Ford Coppola's “Apocalypse Now”. Harry is nothing if not a gumshoe Kurtz, the warrior of terrifying metaphysical resolve who breaks the laws of the flabby liberal democracy in order to save it. Society as depicted in Siegel's film—the mayor, the press, the people—neither makes a hero or a scapegoat of Harry, though at times he is close to both. Instead, Harry's relationship to the world around him is characterized by uneasy ambivalence. He is always on the brink of disavowal.

In fact, not only is “Dirty Harry” not an overt call for fascism, it displays its surface politics, with frequent and what I can only guess are intentionally comic touches, in a manner that actually satirizes them. As seriously as “Dirty Harry” tries to parse problems pertaining to civil rights, the film often veers into outrageous caricature. The setting of the story is San Francisco, among the most nauseatingly, exhaustively liberal cities in the U.S. Unsurprisingly, here and there the police are villified as “pigs”. There is a permanent, carnival atmosphere of sinfulness, as if the Sixtiese never ended. Siegel's criminals—even the common muggers!—look like they equate breaking the law with personal liberation and free love. Only in San Francisco, we might chuckle; but that's just it—only in San Francisco.

Scorpio's effeminate nature is contrasted with Harry's manliness all the way down to the sound effects used on their guns. Scorpio's pistol crackles like a bottle rocket, while Harry's booms like a Howitzer. Upon seeing the .44, Scorpio makes a homoerotic remark about the size of Harry's gun. And Scorpio, far from the total lunacy of most serial killers depicted in films, somehow remains lucid and competent enough to jab at every one of the establishment's pressure points, effectively employing the behavior and badges of "the left" so that he comes to symbolize not only West Coast hippie liberality but the national wave of rock and roll, the sexual revolution, and the Civil Rights movement. If Siegel and his writers were making a case for putting a stop to the immorality of the Sixties, how openly stilted it was!

Then there's Harry. It is easy to see that, whatever his virtues, the severity of Harry's morality derives from his sexual frustration. He is less an Achilles than a Peeping Tom wandering in the city's shadows. On a stakeout, he misses Scorpio on the rooftop, at first, because he is watching a naked woman in an apartment below, and when he chases the man with the tan briefcase through the alley he continues watching once it appears he is about to make love to his girlfriend, Hot Mary, even when he realizes the man isn't Scorpio. These are two of the four naked women he sees in the film, the other being sleazy nightclub strippers, which he must suffer while tailing Scorpio, and the dead girl dragged from the ground. Poor Harry! In each case, the overworked, undersexed cop is on duty, figuratively and sometimes literally with his nose pressed against the glass, ruefully watching others enjoy themselves in ways he cannot. He embodies the counter-culture's explanation for evil in the world: repressed white men who take to fascism because they aren't getting any.

Because of the way its subtle satire, so trenchantly funny, eats away at the more superficial message of the need for a quasi-fascist police force to battle excessive liberality, “Dirty Harry” slowly becomes comforting. There is instruction to be had here about a particular frame of mind. To the degree that the film carefully stages the circumstances in which law and order must be subverted to be protected, we see the full scope of the paranoid delusions in which the right-wing mind must wrap its arguments for bypassing the law. Gratifying as a police drama—Eastwood's gruff charm, Siegel's efficient direction, and a lot of unforgettable dialogue make “Dirty Harry” enormously entertaining—the larger arguments are of a hothouse variety: only in such-and-such conditions, in such-and-such a context, would we want or need a man like Harry Callahan patrolling our streets.

This is crystallized in one of the film's funniest lines. Asked by the mayor how he confirmed the true intentions of an alleged rapist he had gunned down the year before, Harry testily answers, “When a naked man with a hard-on chases a woman through an alley with a butcher knife, I figure he isn't out collecting for the Red Cross”. Well, yes. Harry's got a point. The mayor has no argument with that, and neither would anyone else. But the black-and-white evidence of guilt had been giftwrapped for him. The need for careful judgment, adherence to law, and cool-headed, rational analysis must give way to quick, decisive action. But visualize Harry's description. In reality, the conditions which would allow a cop to pass such swift judgment on a criminal occur so rarely as to be negligible.

Thus, instead of strengthening their argument, the filmmakers of “Dirty Harry” actually illustrate how much the argument for breaking the law in the name of a greater good relies on a meticulous effort to manipulate the details before the fact. If “Dirty Harry” reflected the state of the nation in 1971, in 2006 we find in its reactionary hyperbole a mirror of the Bush Administration's creative and often blatantly cinematic pre-arrangement of conditions justifying the subversion of the Constitution. When one side gets to craft the prefatory drama—the alley, the butcher knife, the hard-on—nearly anything can be made permissible. And taking a good look at the story they're currently crafting, which is beginning to look more and more like the business end of a .44 magnum pointed at our faces, there's really only one question Americans should ask ourselves. Do we feel lucky? |

|

| |

|

| |

Back to Essays page.

|

|

|

|