“Green Zone” is an action-movie treatment of the early stages of the Iraq war, focusing on an Army unit chasing Saddam’s stockpile of WMDs in Baghdad after its capture by the Americans. Based on Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s book, Imperial Life In The Emerald City, Brian Helgeland’s lean, fleet-footed script traces the faultline between the military and civilian leadership in the region after the “shock and awe” of Operation Iraqi Liberation (OIL)* in March, 2003. “Green Zone” is an action-movie treatment of the early stages of the Iraq war, focusing on an Army unit chasing Saddam’s stockpile of WMDs in Baghdad after its capture by the Americans. Based on Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s book, Imperial Life In The Emerald City, Brian Helgeland’s lean, fleet-footed script traces the faultline between the military and civilian leadership in the region after the “shock and awe” of Operation Iraqi Liberation (OIL)* in March, 2003.

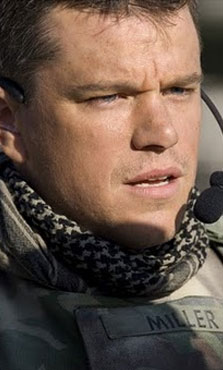

Reuniting the star and the director of the Bourne franchise, Matt Damon and Paul Greengrass, the film combines the robotic toughness of Damon’s rogue CIA agent with the shadowy world of a classic political thriller. The WMDs aren't where they’re supposed to be, and Chief Warrant Officer Roy Miller wants to know why. Repeated run-ins with bad intelligence forces Miller to start questioning why the U.S. is in Iraq in the first place. Miller is a consummate professional, but he still needs the whys behind the orders.

Greengrass throws the audience right into the war, starting with a few establishing shots of an eerie Baghdad night lit up by American ordinance. The images are reminiscent of footage seen on cable news, both in 2003 and the first Gulf War. This call-back, along with Greengrass’s handheld-camera kinetics, gives the film a documentary-style immediacy.

These touches are crucial. The plot of the film is somewhat plausible but its characters are groaningly one-dimensional. That Damon’s warrant officer is all business is understandable, perhaps, but the CIA station chief Martin Brown (Brendan Gleeson), State Department bureaucrat Clark Poundstone (Greg Kinnear), Special Forces goon Briggs (Jason Isaacs), Wall Street Journal reporter Lawrie Dayne (Amy Ryan), and local Iraqi “translator” Freddy (Khalid Abdalla) never rise above the level of clunky interlocutors there to swell a progress or two. They are as thin as the Iraqi Most Wanteds on the infamous deck of playing cards, values and ranks rather than people. Greengrass’ gripping, realistic style is necessary to sell “Green Zone”’s claims to truth when its wafer-thin characters can’t.

In fact, the thin characters aren’t a knock on Helgeland’s screenplay at all. On the contrary, “Green Zone” is bracingly adroit in attaching skin and bone to weightless wisps of information that have until now tended to slip into the abstract. The characters are thin personifications of various speculative positions about the war and in that sense serve a valuable purpose.

Take Freddy, the all-important “human face” of the Iraqi people. He is merely a placeholder for the larger mass of citizens he is meant to represent. And yet Abdalla’s incendiary performance convinces us of his decency, his patriotism, and his passionate quest for justice. He becomes something of a positive stereotype in a film that tacitly allows for the necessity of stereotypes in the examination of a subject too broad to cover in a single two-hour feature. Helgeland has made a barebones translation of non-fiction into a decently exciting action thriller. A swarm of unruly details is slowed down to coherence, at least long enough for the audience to understand that Iraq, for the Americans anyway, has never been, and never will be, anything except a swarm of unruly details.

What of those details? A central criticism made by “Green Zone”, expressed by way of a long, gritty, suspenseful manhunt, is that the Americans blew it almost immediately by disbanding the Baathist-dominated Iraqi army. Lacking sufficient forces to ensure the peace, the U.S. let Iraq fall victim first to chaos and looting and then to the fragmenting of the citizenry into hardened factions.

The reason for this failure is perhaps the more important point Greengrass attempts to make. The military forces, civilian command, and CIA were not on the same page—and not by accident. Kinnear is the film’s villain, an oily Washington idealogue in the mold of a Wolfowitz or a Feith. He’s convinced that Washington’s larger vision for the Middle East sometimes demands that certain corners be cut, certain half-truths floated. Reality is a nuisance to be swept aside by the neocons in Washington who believe that backing bold political idealism with invincible muscle eliminates the need for inconvenient scruples about truth, justice, democracy, etc. Smartly, Kinnear doesn’t play Poundstone as a ruthless mastermind. He’s a bright go-getter, not so much a Machiavellian schemer as a post-grad testing a theory in a giant real-life laboratory; in Rumsfeldian terms, Poundstone is a long way from knowing what he doesn’t know.

Miller, on the other hand, senses the size and shape of the gap in his understanding. It looks something like the ghostly figure of Magellan, at first a cipher and then, gradually, a figure who comes to resemble the Iraqi general who was said to have given the Americans the irrefutable proof that Saddam’s WMDs were safely hidden from the United Nations. The search for General Al Rawi is as expertly handled as anything in the Bourne films.

The final sequence, in which Miller rushes to reach Al Rawi before Poundstone’s hit squad, is almost uncannily frightening. Baghdad is filmed as a Joycean night-town outside the Shangri-La of the Green Zone. The curfew-emptied streets are eerily silent. The un-powered buildings are pregnant with invisible hostility. A stray dog trots along in the street. Greengrass’s cinematography, which uses video, slathers the low-lit city in a garish sodium smear. While Al Rawi’s fate is a reminder that more complicated lines of abstract thinking have been distilled into A-B-C blocks of drama, the resolution of the chase gives the movie the satisfying, harrowing, tragic finale it has been aiming at since the opening credits.

It is not the last scene in the film. Miller returns to his base-camp in one of Saddam’s old palaces to write a damning report detailing the mis-steps and malfeasance of Poundstone and his minions. Miller turns in the report to Poundstone, who of course dismisses it scornfully. Poundstone knows Miller won’t get in the way. But Miller also emails a copy of the report to Lawrie Dayne, the WSJ reporter who argued forcefully for the existence of Saddam’s WMDs in the lead-up to the war. She had shilled for the White House based on unverified information fed to her by Magellan via Poundstone.

Now Dayne is haunted with guilt, since the information looks more and more dubious with each new WMD site turning up empty. She smiles to see the report in her Inbox; the smile widens when she notices that Miller has copied a dozen of her colleagues. Greengrass gives us a closep-up of the screen so we can read the email addresses: CNN, NBC, ABC, The New York Times, and so on. “Let’s get the story right this time”, Miller writes, the forthright and honorable soldier he is.

Miller’s email sailing out into the world to “blow the lid off” Washington’s poisonous brew of incompetence and lies is intended to be a payoff along the lines of, say,“All The President’s Men”. Greengrass has given us two hours of truth. Now the focus shifts to the transmission of that truth to the world outside. Miller copied a handful of journalists in his email. Greengrass has copied the rest of us. We are now privy to the truth about Iraq. The pretexts for war were phony. The execution of the war-plan was fatally flawed. And the men responsible for all this have gotten away with it. So far, at least.

In essence this is very much like the closing scene in “The Matrix”. Here’s the truth about your world, Neo tells us. Now it’s up to you to act on what you’ve learned. It is difficult to tell if “Green Zone” intends this ironically or not. Does the information it passes along to us qualify as a bombshell? Really? The truth about the Iraq war has been available in clear, no-nonsense form to the American people long before this film was released, and for that matter a few years before Chandrasekaran’s book was published.

It’s tempting not to take this in earnest and instead read “Green Zone” as an acid commentary on those who manufactured the war (Washington) and those who sat back and let it happen (you and me). The naive notion that Miller’s report would have changed anything, especially sent to mainstream journalists, would be riotously funny if it weren’t also tragically mistaken. They journalists did know. They didn’t utter a peep. We knew. Most of us didn’t lift a finger of resistance.

Greengrass’s joke, if it is indeed intended as a joke, is having built a Hollywood action-thriller around a mystery that has never actually been a mystery. “All The President’s Men” was an account of the unveiling of a troubling political secret. “Green Zone” gives us stick figures working to uncover a troubling political secret that has been hiding in plain sight for seven years—at least seven years, since many predicted the absence of WMDs before the invasion and had long warned of the dangerous civilian leadership running the American war machine.

Miller’s revelation, in short, is no revelation at all. The film can be seen as a caustic indictment of the American people’s need to have the truth spoonfed to them in the forked-up sugary mush of a Hollywood action movie. Facts aren’t enough. Thinking’s a drag. We need Matt Damon to adrenalize the truth, pump it up to action-movie levels before we can see what’s in front of our noses. The final twist being that even in this pulpy, digestible, spoonfed form the truth about the war in Iraq will be greeted with a roar of crickets.

______________________________________

*Washington’s original branding of the war was indeed OIL. Ari Fleischer used this appellation on two separate occasions before someone alerted the White House to the obvious implications of slapping the acronym “OIL” on its valiant war to spread freedom and democracy. The acronym was quickly changed to “OIF” (Operation Iraqi Freedom). To complete the Orwellian prestidigitation, the White House later deleted all traces of Fleischer’s press conferences. Officially OIL never existed.

|